Welcome to my chaotic experiment –

Cultivating our sourdough starter

All of my life I have enjoyed a good scientific endeavor. I was definitely one of those kids who would waste up all of the shampoo and soaps in order to make new concoctions to see what would happen with them, eventually resulting in nothing much more than wasted products going down the drain. As I aged and with my education, I was introduced to other types of science experiments that tied in my unending curiosity with the other things I loved, primarily eating good foods.

I was introduced to the concept of food chemistry by my sophomore year microbiology professor who loved to talk about fermentation. She positively beamed when she was given the opportunity to discuss the why and how bacteria and yeast, when in the right proportions, worked together to bring us new foods. I vividly recall being in our college lecture hall surrounded by pre-health and nursing students, we were just experiencing the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the subjects of her entire life’s work was being called into question. For lack of a better term, microbes were getting a bad rap. My professor, as sweet as she was, was always very adamant to note that “bacteria don’t want to hurt us, they just want to live!”

Back in college, I dabbled with fermentation of Kombucha. I am pleased to say that it worked, however TERRIBLE it tasted. I would have kept it up for longer, but the scent of vinegar was a problem in a shared household, so kombucha was put on pause.

This time around, we are trying out something a bit more amenable to a nice smelling home, sourdough!

What is Sourdough?

Sourdough is a type of bread product that is the result of cultivation of wild yeasts and bacteria that are found in our environment. Bread, as we typically know it these days, is made by combining baker’s yeast (our leavening agent) with warm water in order to “bloom.” We then add dry ingredients of our choosing and allow that bread to rise at least once. This product is zhuzhed up to the baker’s preference and allowed to bake.

Sourdough functionally follows that same recipe, except our leavening agent is our wild yeast/bacteria culture, which we will refer to as a starter. It is also referred to as a bread mother, levain, or as famously written in Bourdain’s Kitchen Confidential – “the bitch.”

People who do sourdough are cult members in their own way – you create a starter out of nothing but flour and water, and then the rest of your life, worship at its altar.

For this experiment, I will be documenting the day by day process of my sourdough starter development for all one of you (hi, Honey) that will read this post.

What is the microbiology at play here?

Sourdough starter is one of the oldest forms of leavening agents that humans have cultivated. Commercial, rapid fermentation yeast, the stuff we can buy easily in packets at the grocery story, have only been around for the last 150ish years. When we create a sourdough starter, we are harvesting natural yeast and bacteria from our environment and giving them an optimal environment to flourish.

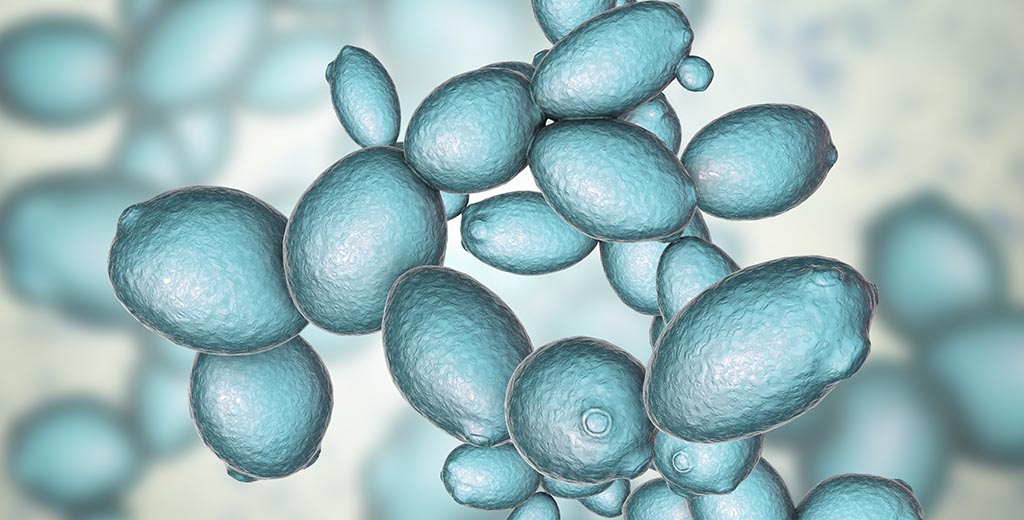

Our primary yeast that we cultivate is a species called Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which is colloquially known as baker’s yeast. In order to reproduce, S. cerevisiae processes simple carbs into CO2 and ethanol. This is the same process of fermentation that occurs in production of alcohol and kombucha. The CO2 “put off” from the yeast fermentation gets trapped in the dough, which creates a gluten matrix and expands our dough. While S. cerevisiae is our primary yeast, there can be upwards of hundreds of other yeast species present.

The goal bacteria in our starter is Lactic Acid (LAB). These bacteria are present in decomposing plants, dairy, fruits and veggies, and on the surface of the human body. LAB in our starters typically outnumber yeast by upwards of 100:1. Lacto-fermentation, the process of preservation secondary to LAB presence, creates an acidic environment which serves us two-fold: the acid develops a sour flavor, which produces its unique flavor, and keeps away unwanted pathogens. LAB also releases protease enzymes which break down gluten over time, thus resulting in the soft interior of sourdough that we know and love. This is why sourdough is inherently lower in gluten compared to breads made with rapid fermenting yeast, since sourdough takes its sweet time, more gluten is broken down. The process of lacto-fermentation is also present in the development of foods such as kimchi and sauerkraut.

In my research, I learned that there are largely two group classifications of LAB that are present in sourdough: Homofermentative and heterofermentative.

- Homofermentative LAB only produce other LAB during fermentation. These LAB create flavors that people typically identify as “creamy.” These bacteria include: Streptococcus, Lactococcus lactis, Enterococcus, Pediococcus, and L. acidophilus.

- Heterofermentative LAB produce lactic acid, acetic acid, ethanol, and CO2 during fermentation. This amplifies the leavening process alongside our yeast cultures. Flavors with these strains of LAB create the “tangy” flavor in some sourdoughs. These bacteria include: L. plantarum, L. fermentum, and some others.

Sourdough starters can live for as long as they are fed and cared for. Over the course of its lifetime, many species of LAB and yeasts can colonize and take control depending on the type of feed and temp its held at. Over time, however, starters tend to become colonized by the more stable heterofermentative LAB such as L. fermentum and L. plantarum. As these colonies find their home in our starters, the sour flavor tends to become stronger.

A FUN FACT!

The famous san francisco sourdough is named as such because of its primary colonized species of bacteria (L. Sanfrancisensis)!

Now lets get to the fun stuff…